The Painted Cat, by Austen Crowder – book review by Fred Patten.

by Patch O'Furr

Submitted by Fred Patten, Furry’s favorite historian and reviewer.

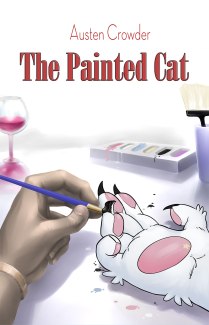

The Painted Cat, by Austen Crowder.

Dallas, TX, Argyll Productions, April 2015, trade paperback $19.95 (273 pages), e-book $9.95.

“I started painting myself up to look like a toon for two reasons. First, I was bored and needed a new hobby during my summer break as a teacher. Second – and far more important, in my opinion – was that my friend Valerie thought I’d look good as a cat, and I had always wondered what could have been if I had turned toon like she did. That she brought all the supplies, prosthetics, and paint we could possibly have needed sort of sealed the deal.” (p. 9)

The Painted Cat is more like Gary K. Wolf’s 1981 novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit?, or Disney’s 1988 Who Framed Roger Rabbit movie based upon it, than the average anthropomorphic novel. It omits the Disney crazy comedy, but in this world, the toons – and they are called toons — are live cartoon animals, not anthropomorphized “real” animals, who are socially lower-class living among humans; plus those humans who turn themselves into toons with special paint and prosthetics – see the deleted “pig head” sequence from the Roger Rabbit movie. Janet Perch, the protagonist, straps on a cat tail very like the artificial fox tails on sale at every furry convention, and within moments it attaches itself to her spine and she can move it like any cat can do with its tail.

What’s more, toon-ness is a disease-like condition among humans that causes some to transform during their adolescence. In Chapter 2 Janet, a middle-aged human schoolteacher, is talking with another teacher about their concern for a student who is turning into a toon squirrel, and their own secret liking for toons:

“We lost ourselves in thought over Nathan. I tried for a moment to imagine just what went through a parent’s mind when they threw their son out of the home. Tough love, maybe? A fear that that toon-ness may rub off on them? Maybe the parents felt like a failure; that the kid’s toon-ness was just a failure that showed just how bad they were as people, and the only solution was to disavow any knowledge of that child actually coming from their household.” (p. 20)

and:

“He took a deep breath. ‘That stuff can get you fired if you were caught. It shouldn’t, mind, but you know how it is. Help kids who are turning toon, sure. The administration looks the other way. It’s at least humane to give those kids a shot. But having one of their teachers go out and paint themselves up for fun?’” (p. 22)

Well, the toons don’t exactly live alongside the humans. They have their own lower-class neighborhoods, more like those in Wolf’s original novel than the zany Toontown ghetto in the Disney movie. And they’re in the majority in the city of Clampett where much of The Painted Cat takes place.

“You see, life in Clampett is a little out of the ordinary. Sure, there’s all the quirks and perks of a modern city there: plenty of great food, theater, taxicabs at every corner, late night rooftop parties, the whole nine. That’s all pretty standard. What is weird about Clampett is that it’s inhabited almost entirely by toons. Not painted like Bunny Cat, but real, in-the-flesh cartoon animals. It was the kind of place where you could get into a taxicab driven by a walrus, have shawarma served by an elephant, and then watch a troupe of meerkats perform MacBeth in the park.” (p. 10)

Janet Perch is human. Her best friend Valerie turned into a toon cat during high school. She was thrown out of home by her parents and became Valerie Cat living in Clampett’s Jazztown district. Janet didn’t cut her off – well, she did temporarily — and they’re still best friends, although Janet is discreet about visiting her there. Janet finds that she likes Jazztown:

“Around and around we went, sliding past elephants at tables, dogs and foxes dancing in streets, the occasional giraffe serving martinis to rooftop patrons. Humans mingled with toons; toons mingled with humans in halfway stages of transformation; and above it all was a cacophony of noise, squealing trumpets and punchy basslines, syncopated to the rhythm of a fast-talking, progressive-thinking group of deviants who took great joy in giving the real world the finger.

I won’t lie: the whole mess struck me as romantic.” (p. 25)

There are live toon vehicles like Disney’s Benny the Cab, too, but without the zaniness. Toons, whether cartoon animals or vehicles, don’t need to eat; conveniently if they don’t have naughty bits. (They may not have digestive tracks, either. I don’t know how that works.) That’s the setup. The story is about how Janet Perch, a bored middle-aged human teacher among the human inhabitants in nearby Irving, lets her best friend Valerie Cat talk her into painting/disguising herself as Bunny Cat to lay back on weekends and enjoy life among the toons of Jazztown.

Then Valerie leads them out of the night club district.

“‘Still with me?’

‘Yeah. Party’s back there, though. Weren’t we going to, you know, stop for a club? That’s kind of the point of going out last I checked.’

She flashed me a smile. ‘That stuff’s for tourists on the weekends. Fun for a bit, but if you meet real toons you kinda have to get off the beaten path.’

‘I don’t understand.’

She looked around for a moment. Her lips twisted with what to say next. ‘I was thinking about what you said in my apartment. About… well, wanting to be a toon.’” (p. 26)

I could use up this whole review talking about the world that Crowder describes.

There’s toon sex:

“I’d never understood how that whole toon sex thing worked anyhow; none of my toon friends had the parts and pieces for tab-a-into-slot-b sex after they’d changed over.” (p. 35)

Clampett also has an Anime district:

“‘Then there’s the Anime district, where it’s all slow motion and lens-flares and crap. You don’t even say anything to each other; you just stare deeply into each other’s eyes. Sometimes one of you gasps and turns red and that’s it.” (p. 50)

Everybody there looks like pre-teen kids with huge eyes, but they have the parts and know how to use them. There’s Canadatown with lumberjacks and log-drivers and poutine, eh?

Janet learns that if humans can use special paint & prosthetics to pass as toons, so can toons to pass as humans outside Clampett, and – Yarst! I’m giving away spoilers, aren’t I?

Gary K. Wolf and the Disney studios invented living cartoon animals and vehicles in the Roger Rabbit books and animated films. Now Austen Crowder is using that fantasy world, but for a serious novel, not a zany comedy. It works much better in zany comedies, where the serious mood doesn’t prompt you to wonder how things work. Still, Crowder tries his best.

Janet Perch is living two lives. She lives and teaches in the humans-only (Whites-only) town of Irving. Her personal liking and sympathies are for the nearby toon/Anime/whatever town of Clampett. Despite that letting her preferences become known in Irving could get her fired and crosses burned on her lawn, she risks going into Clampett and painting herself as the free-spirited Bunny Cat (see the cover by Evan Appel) to join her friend Valerie and become two female toon cats on the town, living the good life. When Irving’s Get Real (Ku Klux Klan) society starts dictating the curriculum that she is required to teach her students in Irving, she realizes that she can no longer live two lives. She has to choose one or the other. But will either the toons or the humans believe that her choice is sincere? Especially if it isn’t? No matter, when Janet discovers that it’s too late to make a choice now. Now it’s a question of whether she can escape to where she really wants to live in time.

The Painted Cat is a different novel; not quite successful, and too heavy-handed in both its message of tolerance and in its bias. But it’s still worth reading for its colorful picture of a toon society without the slapstick humor.

This is an “opinion”, but I do not think a lot of people could relate to this book’s premise.

That’s niche fan publishing for ya. 🙂 To me, it sounds like it spins out a very involved fantasy scenario with a premise that’s meant to be absurd and impossible, and I can only applaud the effort.

Surrealism dealt in the irrational and paradoxical, and you can graft storytelling mechanics on it and get works of art that read like other stories but are closer to abstract art. One of my favorites is JG Ballard. Ever read him? I’d go as far as to call him the most artful science fiction writer… he notoriously wrote things like Crash, the novel about people “becoming sexually aroused by staging and participating in car crashes.” His premises barely resembled anything you can relate to but they’re amazing experiences.

Sooo anyways, I like when writers reach past the usual. 🙂